Hey, I'm so glad that this blog is the number two source for Google searches on "inane in sentence."

Sorry about the lack of pictures for the "housewife 1 on 1." And (presumably), on the other end of a gender continuum, who Googles "my husband is an asshole" and expects advice?

Apparently I'm also the go to blog for people that spell patriarchal as "patriartical". Good to know, thanks StatCounter.

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

Monday, September 24, 2007

A Wrinkle in Time

I reviewed the classic children's book A Wrinkle in Time* over at the Newbery Project yesterday. Why did I wait over thirty years to re-read this book?

I reviewed the classic children's book A Wrinkle in Time* over at the Newbery Project yesterday. Why did I wait over thirty years to re-read this book?I like the cover on this edition better than the one we have at home. I'm going to buy a nice hardcover edition for my kids (ok, for me really), because we should have this on our shelves.

*edited 9/27/07 to add a link to And Another Thing about A Wrinkle in Time...

Saturday, September 22, 2007

Learning to Drive: Book Review

In the last year, I've read all of Pollitt's essay collections (and blogged here about Virginity or Death! and Reasonable Creatures). I enjoy Pollitt's political perspectives and her humor a great deal, but it's her incredible gift for words that really keeps me reading, even when she's writing about a topic that doesn't particularly interest me. The pace, the particular words she picks, the way it all hangs together, often ending with a surprise punch to your gut - it is all very satisfying. And of course it helps that I agree with most of Pollitt's views - it's always nice to find your opinions vindicated by someone who articulates what you were thinking with such color and style.

Anyway, this is a long-winded way of saying that I was really looking forward to Pollitt's new book, especially when I read that it was mostly material that was not previously published (many of her essays for The Nation can be read online here and since I got hooked, I've been reading the columns and her blog regularly). And not only is this book new stuff, it's more personal than political, which makes it quite different from her previous works.

Some reviewers apparently feel a bit betrayed by this. The most brutal review was by Susan Salter Reynolds in the LA Times, who called the collection "whingeing" and "self-indulgent at best". I don't agree (but do agree when Reynolds says "It must be my problem"); I think that Pollitt's honest and sometimes painful essays about her personal relationships, fears, and aging make for utterly compelling reading.Unlike her previous books, which I picked up and put down, reading an essay every couple of days, I read this one in a day and a half, stealing moments whenever I could find them to read the next piece. It was over all too soon.

Here's a few selections from my favorite parts. On the aftermath of her breakup with a long-term boyfriend, who lived with her for years and apparently slept with numerous other women:

...I would browse the Internet, searching for information about him. Except "browse" is much too placid and leisured a word - a cow browses in a meadow, a reader browses in a library for a novel to take home for the weekend. What I did fell between zeal and monomania. I was like Javert, hunting him through the sewers of cyberspace, moving from link to link in the dark, like Spider-Man flinging himself by a filament over the shadowy chasm between one roof and another. "Are you Webstalking him?" a friend in her twenties asked over coffee. I hadn't known there was a word for what I was doing. (p. 22)

On what people do vs. what they say, and the power and beauty of words:

You think what people say is what matters, an older friend told me long ago. You think it's all about words. Well, that's natural, isn't it? I'm a writer; I can float for hours on a word like "amethyst" or "broom" or the way so many words sound like what they are: "earth" so firm and basic, "air" so light, like a breath. You can't imagine them the other way around: She plunged her hands into the rich brown air. Sometimes I think I would like to be a word - not a big important word, like "love" or "truth," just a small ordinary word, like "orange" or "inkstain" or "so," a word that people use so often and so unthinkingly that its specialness has all been worn away, like the roughness on a pebble in a creek bed, but that has a solid heft when you pick it up, and if you hold it to the light at just the right angle you can glimpse the spark at its core. (p. 31)

As a midwesterner, I loved the insights into New York City and the east coast in general (no strollers in post offices? What are they, crazy?), especially when it came to motherhood and feminism:

And it was feminism that made it an expected, an ordinary, thing for a man and a woman to live together in their own way - they could clean the house together or just let it fall apart. Those were not ideas that you could easily derive from middle-class American family life in the 1950s and 1960s, even a family of Communists like mine. Who owned the means of production - that was nothing, that could change overnight. But who vacuumed, who brought coffee while the other person remained seated, who held forth and who made encouraging murmurs - that seemed set in stone. (p. 171-2)

I hope that people who don't read Pollitt's columns will pick up this memoir - which veers from funny, to touching, to nostalgic, and then back again to funny - and go on to read the rest of her work. As for me, I'll be returning my copy to the library, buying my own hardcover copy, and hoping that Pollitt comes on a book tour to Ann Arbor so I can get her to autograph my book.

Tags: Katha+Pollitt, books, book+review, Learning+to+Drive

Monday, September 17, 2007

Americans and Food

The Americans are the grossest feeders of any civilized nation known. As a nation, their food is heavy, coarse, and indigestible, while it is taken in the least artificial forms that cookery will allow. The predominance of grease in the American kitchen, coupled with the habits of hearty eating, and of constant expectorations, are the causes of the diseases of the stomach which are so common in America. -- James Fenimore Cooper, in The American Democrat, 1825 (cited and disagreed with by Frederick Marryat in his A Diary in America, 1839, on p. 30 of the book below).

Just a tidbit from American Food Writing: An Anthology with Classic Recipes, edited by Molly O'Neill. I don't think we can say that modern American cooking is not artificial in form any more (and isn't it interesting that "artifice" is considered a good thing in 1825?), and expectoration doesn't seem to be such a huge problem any more (are they talking about spitting chew? Just spitting?), but we've certainly still got the grease and heavy eating going.

Just a tidbit from American Food Writing: An Anthology with Classic Recipes, edited by Molly O'Neill. I don't think we can say that modern American cooking is not artificial in form any more (and isn't it interesting that "artifice" is considered a good thing in 1825?), and expectoration doesn't seem to be such a huge problem any more (are they talking about spitting chew? Just spitting?), but we've certainly still got the grease and heavy eating going.This book is amazing. It's perfect for browsing - over 700 pages of wonderful excerpts from everyone from Thomas Jefferson, H.L. Mencken, Betty MacDonald, Peg Bracken, and David Sedaris to Michael Pollan, organized historically, a with wonderful section of sources and a meticulous index that starts at abalone and ends at Zuni breadstuff.

A lot of my favorite authors are in here. Frederick Douglass talks about ash cakes and hunger, Walt Whitman describes feeding ice cream to wounded soldiers in a Union hospital in Washington, D.C., and Emily Dickinson provides a recipe for her favorite cake. John Steinbeck talks about breakfast. Russell Baker describes franks and beans. Wendell Berry, Raymond Sokolov, Daniel Pinkwater- all here, as well as any famous food writer you can imagine.

The only problem with this book? It's so big that I'm not going to be able to finish it before it's due back at the library. Ah well, I really need a copy of my own to be able to consult whenever I need it. Did I mention that the recipes that interleave the excerpts are historically intriguing, often droolworthy, and that someone with a wonderful sense of graphics and balance arranged these recipes?

Sunday, September 09, 2007

Fossil Park in Sylvania, Ohio

Fossil Park, just south of the Ohio-Michigan border, is a great place to take your kids on a fall weekend. It's free, you get to keep all the fossils you find, and all you need are some buckets and old toothbrushes (and maybe sunscreen, drinking water, and mosquito spray). They supply the fossils (crinoids, tons of different species of brachiopods, horn corals, and some trilobites) from the Devonian seas, portajons, and a couple of friendly college students who are knowledgeable about local geology and ecology.

Even a five year old can break apart the chunks of shale and recognize the shells within, though they may not have the endurance needed to keep going long enough to find a trilobite. Every time we've been there, though, one of the regulars has shared some broken trilobite bits with my enthusiastic ten year old, who in turn shares his knowledge of paleontology with anyone who will listen.

-edited in Aug 2009 to fix the park system's link, and to add that Google Maps doesn't take you to the right location when you enter "Fossil Park, Sylvania, OH" in their search box. The park is located at 5705 Centennial Rd. (just south of where it says "Silica Quarry #1 on the Google Map), down a little gravel road on the right when you're heading south, just past the Mayberry Square stripmall (which is on your left). If you're coming from Michigan, exit US-23 at Sterns Rd. - the last exit before the Ohio border - and take Sterns Rd. to Clark Rd., which turns into Centennial Rd. in Sylvania.

Wednesday, September 05, 2007

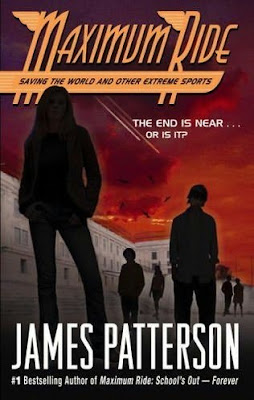

Maximum Ride #3: Book Review

Generally, I only post reviews of books that I either absolutely love and want to share with the whole world, or books that annoy me so much that I don't want a single other person to waste their time with them - even with used copies that are "free with shipping & handling" online. Reviews are surprisingly easy when you have such strong feelings about a book.

Generally, I only post reviews of books that I either absolutely love and want to share with the whole world, or books that annoy me so much that I don't want a single other person to waste their time with them - even with used copies that are "free with shipping & handling" online. Reviews are surprisingly easy when you have such strong feelings about a book.But then I sold out (see here), and starting taking remuneration - in this case, an amazon.com gift certificate, as well a free copy of the book, from the savvy women at MotherTalk. The first book that came my way was James Patterson's Maximum Ride: Saving the World and Other Extreme Sports. I thought I was pretty well qualified to review this book.

I'm not a literary snob (I love good romance, chick lit., and mysteries), I read lots of current bestsellers, and one of my favorite genres is fantasy/sci-fi. In the last year I've been reading lots of children's and YA selections, reviewing lots of different kinds of kids' books for The Newbery Project. One of the most recent Newbery winners that I read - Robin McKinley's The Hero and the Crown - reminded me of just how much I like fantasy, and since Patterson's Maximum Ride series is aimed at about the same age group (12 & up), I was really looking forward to it.

Well, if I'd picked this up on my own - perhaps to see if it was appropriate for my ten year old (and it was, for the most part), I wouldn't have bothered with a review. It was just....well, totally (to the max?) mediocre.

I didn't hate this third installment in the Maximum Ride series. I was intrigued by the premise: a group of runaway gene-engineered kids with wings save the world from evil mega-corporation scientists. I actually sought out Patterson's almost-parallel adult book, which I somehow completely missed nine years ago. (Maximum Ride was spun off Patterson's When the Wind Blows).

I didn't finish When the Wind Blows, though. Even the addition of sex didn't make up for a way too-predictable story and clichéd characters. And after reading about half of When the Wind Blows, I definitely felt like Maximum Ride was the better book. During both books, I felt like I was reading one of those X-Files or Star Trek adaptations, with a couple hundred extraneous pages of padding - mostly witty banter and stereotyped descriptions of laboratories. In fact, I can imagine the (proposed) movie, with its cool CGI graphics and nearly non-stop action.

I did enjoy many of Patterson's descriptive passages, and I can see how his writing style would appeal to most teenagers:

Well. If sudden knowledge had a physical force, my head would have exploded right there, and chunks of my brain would have splattered some unsuspecting schmuck in a grocery store parking lot down below. (p. 94)

"Okay, the second they undo us, make sure all heck breaks loose," I said when everyone was awake the next morning - at least I figured it was morning, since someone had turned the lights on again." (p. 115)

But was it really necessary to substitute heck for hell here? I mean, he's talking about evil experiments on children. If you're old enough to read about that, surely h-e-double hockysticks is old hat. Teenagers are supposed to be reading this, not second graders (though I'm sure quite a few second graders know the world hell, too). It grated on me, like many other things in the book.

I couldn't help liking Max, the main character, who was snarky and plucky and strong. But really, she needed some depth. And what's with the two to four page chapters? It makes it easy to put the book down and pick it up again later, but it was the literary equivalent of commercial tv - a book of sound bites.

Furthermore, I'm a little sick of the evil scientist stereotype:

I won't describe the scariest things we saw that morning, 'cause it would depress the heck out of you. Let's just say that if these scientists had been using their brilliance for good instead of evil, cars would run off water vapor and leave fresh compost behind them; no one would be hungry; no one would be ill; all buildings would be earthquake-, bomb-, and flood-proof; and the world's entire economy would have collapsed and been replaced by one based on the value of chocolate. (p. 337)

Do you really think that our world would be perfect if scientists were better people? What about politicians and company wonks and half the people who voted in the last presidential election? Didn't Patterson see Who Killed the Electric Car? Don't go blaming the scientists, people.

Anyway. If I were giving this book a grade, it would get a solid C. I wouldn't discourage any teenagers from reading it - I'm solidly in the "almost any reading is good reading" camp, and there's nothing really offensive in this book, and plenty to redeem it - but there's nothing really great in it, either. Steer your kids to Jumper, by Steven Gould, or Sunshine, by Robin McKinley, either before or after (or instead of) reading Maximum Ride. That's the kind of YA fantasy that's worth keeping on your shelves and re-reading.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)