Last year, this included The Known World, by Edmund P. Jones (the story of a slave-owning Black freedman and his family); and Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith, by Jon Krakauer (the story of a Mormon family, and how two horrific murders were related to historical and modern revelations, polygamy, and patriarchy).

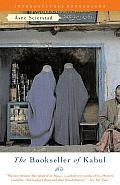

This month's selection - The Bookseller of Kabul, by Asne Seierstad - was not at all what I expected.

This month's selection - The Bookseller of Kabul, by Asne Seierstad - was not at all what I expected.Perhaps this is because in the past year I've read a couple books that are set in the Middle East that were much more literary in style: Crescent, by Diana Abu-Jaber (though most of Crescent is actually set in Los Angeles, many passages take place in Iraq), and Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books (obviously set in Iran), by Azar Nafisi. I thought both were very good books, in very different ways. The authors are both extremely skilled with language and symbolism and all those literary things I vaguely remember from school.

Asne Seierstad is journalist, however, not a professor of English or literature (like Abu-Jaber and Nafisi), and it was surprisingly refreshing to read a straightforward account of her three month stay with the family of a bookseller in Afghanistan's capital.

The Bookseller of Kabul reminded me of an unusually well-written ethnography - an anthropologist's description of a particular culture. Seierstad immersed herself in this family's life: she ate with them, slept on a pallet beside the other unmarried women, wore a burka, went to the market, and helped prepare for a wedding with the women. Because of her status as a Westerner (not a regular "woman"), she was also able to accompany the men to work at the bookstore, on family visits, on business trips, and a religious pilgrimage. The different family members are intimately portrayed; the stories are fascinating, shocking, and sometimes unbearably sad. Seierstad's simple and matter of fact prose perfectly suits the setting and the stories.

The only thing I found truly lacking was a good map of Afghanistan and Pakistan, so I could look at the cities and places described. Luckily, National Geographic's map site filled most of the gaps, showing both cultural and geographic features. It would have been wonderful to also see actual photographs of the people involved - but I can see that would not have done much to keep them anonymous.

Apart from understanding a bit more about what it would be like to live in Kabul, to live in an extanded family, to be a man vs. a woman in Afghanistan, a few things that will stick in my mind from this book are some of the Taliban's rules for proper behavior. I never knew that washing clothes in the river, fighting pigeons, flying kites, playing drums, and virtually all music and dance was outlawed during their regime. And the images of the bookseller's books burning in the street in front of his store - several times over the years - is an appropriate one to think about this week, which is Banned Books Week here in the US.

1 comment:

I'm reading Under the Banner for my book club this month... Facinating.

Post a Comment